Hilary Mantel is the two-time winner of the Man Booker Prize for her best-selling novels, Wolf Hall, and its sequel, Bring Up the Bodies—an unprecedented achievement. The Royal Shakespeare Company recently adapted Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies for the stage to colossal critical acclaim and a BBC/Masterpiece six-part adaption of the novels.

The author of fourteen books, including A Place of Greater Safety, Beyond Black, and the memoir Giving up the Ghost, she is currently at work on the third instalment of the Thomas Cromwell Trilogy.

Mantel delivered this year’s Reith Lectures which will be broadcast this month on the BBC.

Some publications asked for a line or two near the beginning so that their readers wouldn’t be immediately at sea. If you like, you might include something like the text below. Please feel free to amend accordingly:

As part of The Creative Process exhibition and educational initiative traveling to leading universities, interviews with writers and creative thinkers are being published across a network of university and international literary magazines. The Iowa Review is proud to partner/collaborate with/be taking part in The Creative Process' interlinking online exhibition.

< Continued from Tin House

THE CREATIVE PROCESS: I’m interested in your writing process. You’ve described a non-linear approach, your novels as evolving from disparate scenes, perhaps closer to the process of a playwright or screenwriter. Also, as you were discussing before, your books are strongly visual and rooted in a character’s POV.

I mentioned I would be interviewing you to my theater friends and they all enjoyed your work. I mean, some of them don’t read a lot of novels because they think they don’t have enough drama or they’re too interior, but your books gripped them immediately. They like the way your exposition is embedded in the character’s experience and doesn’t slow the action in a way that feels uniquely suited to theater and television. Do you think this is one of the reasons your books have adapted easily to the screen and stage? At the same time, you write these great characters, you give readers a lot of Cromwell’s interior life, things he cannot possibly say. This must have created challenges for the dramatic production. How did you overcome them?

Are there things you’ve learned from watching actors at work which will make their way into future books?

MANTEL: I hope to write something about my recent experience of theater – a small book, a big essay, who knows? But it seems worth exploring. I’ve always wanted to work in the theater, but my ill-health held me back. You can’t offer yourself as part of a team unless you can keep up with the team. Two years ago I began to feel very much better, and that opened up an opportunity for me.

I do develop my books in scenes, and write a lot of dialogue – though book dialogue is different from stage dialogue, which is different from TV dialogue – and that is different from radio dialogue – I’ve explored all these facets. I think I am covertly a playwright and always have been – it’s just that the plays last for weeks, instead of a couple of hours. An astute critic said that A Place of Greater Safety is alike a vast shooting script, and I think that’s true. It shows its workings. When I am writing I am also seeing and hearing - for me writing is not an intellectual exercise. It’s rooted in the body and in the senses. So I am part-way there – I obey the old adage ‘show not tell.’ I hope I don’t exclude ideas from my books – but I try to embody them, rather than letting them remain abstractions.

In my reading of him, Thomas Cromwell is not an introspective character. He gives us snippets of his past, of memories as they float up – but he doesn’t brood, analyze. He is what he does. But that said, you are right, he is at the center of every scene. With the weapon of the close-up, it was possible for Mark Rylance, on screen, to explore the nuances of his inner life. He is very convincing in showing ‘brain at work.’ He leaves Cromwell enigmatic but - in a way that’s beautifully judged- he doesn’t shut the viewer out.

In the theater, what happened was that Cromwell was on stage the whole time. I think in the first play, he had half a scene off; in the second play, it was about 30 seconds. So nothing happens without him. If he’s not talking, he’s watching. We were immensely fortunate in casting Ben Miles, who had the fitness and the dedication to sustain the role – frequently performing both plays in one day – and who had the intelligence and the charisma to carry the audience with him. He explored the character deeply and he has been my ally in building the third book.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS: You were raised Catholic and went to convent school. Can you talk a little about this and your eventual religious alienation?

MANTEL: Two things happened together, when I was about twelve. First I started to cast a critical eye on the Catholic Church as an institution. Then I asked myself if I believed its teaching, and the answer was no. My disbelief had been growing in the dark, unknown to me.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS: And yet even though you’re no longer part of the Church, religion is an important source of conflict in your books. Why do you think, at a time when more and more of us belong to no religious faith, that religion remains such a fascinating theme?

MANTEL: If you are to write about the C16 you have to be able to understand the centrality of religious belief and the sincerity with which people held their differing views, and the reasons they persecuted each other so assiduously in the name of mercy. I can easily grasp this because religion was so central to my childhood. I took everything in, I was asked to believe, and I agreed.

Nowadays I don’t understand faith too well. But I understand hope. And I think they are more closely related than I once imagined.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS: Has your view of religion changed in the writing of the Thomas Cromwell trilogy?

MANTEL: I’ve acquired a lot of information. I’m not sure if my personal outlook has changed. The trilogy is a work in progress and so am I.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS: I’m really amazed at the suspense you generate out of historical characters and events. How do you do that? Because we know or at least we think we know the outcome, but your novels retain a great element of suspense and uncertainty. As a writer, on a line by line level, it must take great skill to immerse readers to the point that it seems like events can go either way.

MANTEL: It’s simple really: the writer knows the outcome, so does the reader - but the characters don’t. You have to persuade your readers to be in 2 places at once. They can’t suspend their knowledge of what happened – they’re above the characters, looking down on them. But at the same time, if you’ve done your job, they’re moving forward with the characters, inhabiting their world. The suspense grows in the gap; the reader wants to know not so much what happens, as how the characters will react when it happens. The reader has to hold his or her own knowledge in suspension – hold reaction back. That’s what creates tension. You see them rushing towards their fate – you know, you fear for them, but you can’t stop them.

Continue Reading on The Nassau Literary Review >

BRIEF BIOGRAPHY

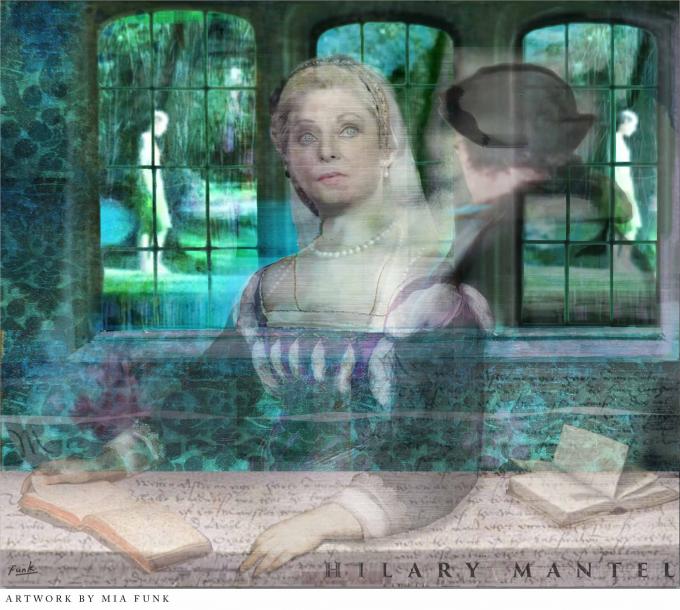

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer, and founder of The Creative Process, an exhibition and international educational initiative traveling to leading universities. Over 100 esteemed writers and 40 universities are taking part in this project. She is currently painting the portraits for the American Writers Museum.

Become a Part of The Creative Process

If this interview has sparked your imagination, find out more.